9.8 KiB

| title | date | subtitle |

|---|---|---|

| How to store passwords | 2020-05-28 | How to store passwords **properly**! |

How to store passwords

Storing passwords is a pretty simple problem in software development, right? Wrong! Storing passwords correctly is pretty complicated. With that said, it's very simple to just lean on work someone else has done, and the libraries available for your language of choice.

In reality, you should never do it yourself. If whatever library or framework you're using can store passwords for you, use it. However, occasionally you'll need to write your own, whether for some specific requirements, or just a keen interest.

So, how should you store passwords?

Plaintext

The simplest way to store passwords is to do just that, store them. Throw the password in your database, and go about your business. Storing passwords this way is quick and easy, both in terms of implementing, and the process of authenticating users.

Authenticating a user becomes as simple as searching for columns where the username is the provided username, and the password is the provided password.

Password reset becomes pretty simple too. If a user forgets their password, you can just email it to them.

Why not?

Storing passwords in plaintext is the worst way to store passwords. If you work in a system which stores passwords in plaintext, please change it!

If you get breached, and your password database is stolen, then the attacker can see everyone's username and password. And because people reuse passwords, this means they can likely access other accounts belonging to the user.

Hashing

A hash is a way of converting one value into another in such a way it's impossible to reverse.

Imagine a smoothie maker. You put fruit in, it mixes it up, and you get a smoothie out of it. Now no matter what you do, there's no machine which could take a smoothie, and give you the fruit back whole. Now yes given a smoothie you could probably tell me which kinds of fruits are in there, but what about which specific fruits? Given a strawberry smoothie, and a picture of a million strawberries, could you tell me which strawberries were in there?

An interesting characteristic of passwords is that that two slightly similar inputs can give completely different answers.

There are many different hashing algorithms, although the most common are the SHA family, specifically SHA265 and SHA512. SHA1 and MD5 are whilst better than nothing, considered insecure. Base64 is not a hash!

When storing a users' password, rather than storing the password, you store the hash. To authenticate, just look for rows where the username is the provided username, and the password is the hash of the provided password.

Why not?

Whilst hashes aren't reversible directly, you can just search for them. Take the value {{< md5 "foobar" >}}. You can't take that value and reverse it back into the input foobar, but you can literally [search it online](https://duckduckgo.com/?q={{< md5 "foobar" >}}) and find the result. This is thanks to rainbow tables.

Rainbow are a huge table of mappings between hashes and their plaintext counterparts. Bruteforcing a hash can take a long time, but looking up a hash in a rainbow table will take a few seconds at most. The rainbow table for seven letter passwords hashed with SHA1 is just 50GB. Project rainbowcrack has a list of them for download.

Hashing also has the drawback of repeatability. Given the same input, a hash will always return the same output. This means that if people are using the same password, they'll have the same hash. Combined with things like password resets, it can become fairly simple to work them out, and fun.

Salting

Want to make your food taste stronger? Add salt to it. Want to make your hashing stronger, add salt to it!

The idea of a salt is to prevent the two main shortcomings with hashing on its own: Users with the same password having the same hash, and rainbow tables. It does this in the same way.

A salt is an additional piece of information added into the hashing process. By ensuring the salt is different for each user, even users with the same password would have a different password hash. Some people use the users email address as a salt, but really it should be a completely random value. The important thing is that it's completely different for users.

The salt doesn't need to be protected in itself, as it's not private information. Given the hash and the salt you're still no closer to working out what the password is, although this time you don't have rainbow tables on your side. You'd need a rainbow table specifically generated for your salt, and if your salt is long and random enough, that's a huge amount of data!

Peppering

Peppering is a technique similar to salting, in that it further strengthens hashes, however it's done in a different way. Rather than using a different salt per user and storing it with the user, peppering uses a single shared key, which must remain private. The objective of peppering is to ensure that even if the database is compromised, there's still missing data which would be needed to perform brute forcing: the pepper.

Why not?

There's a reason peppering isn't well known, and even fewer people use it: It's not very well understood. The hashing characteristics of salting and how it strengthens hashing are well understood, and well researched. Anyone can look at peppering and see "Yes this makes things stronger", but it's whether it makes a meaningful difference.

The other issue comes from the fact it's not well known. If people don't understand peppering, and how it works it'll be implemented wrong or misunderstood. Because peppering isn't popular, there aren't any standard algorithms or libraries which support it, so you'd need to roll your own. Never roll your own crypto!

If you're interested, here's an interesting post on peppering and why it's not really useful: https://stackoverflow.com/a/16896216.

Key Derivation

The point of key derivation is to implement everything I've said above. It takes multiple arguments and derives a single key from it. In this case, a password and salt are derived into a value. PBKDF2, the key derivation function commonly used for passwords, uses a hashing algorithm and runs it multiple times on the password. By running this multiple times, it increases the time it takes to run, increasing the time take to bruteforce values.

Why not?

Key derivation is designed to be slow - Not critically slow, but slow enough. This can add a considerable overhead to any bulk tasks involving passwords. With that said, this is a good thing, and shouldn't be changed or avoided. If you're creating a lot of users during tests, you may get quite a performance improvement by weakening your hashing during tests. I've seen improvements of nearly 30% using just this.

Comparison timing

Once a user has logged in, you've hashed their password using only the best practices, you've pulled what their password should be from the database, it's time to compare them. They're both strings, so == should work, right? Well yes, but actually no. Comparing strings is incredibly well optimised, for good reason! Lots of fundamental parts of programming depend on strings being compared as quickly as possible. However when it comes to security, this isn't necessarily what we want.

Many methods of string comparison have a number of cases to short circuit, and run faster than a regular character-by-character comparison. Even then when running a character-by-character comparison, it's good practice to abort as soon as you've got one character which doesn't match. When comparing hashes, these short circuits are counter-productive. By accurately measuring how long the system takes to check your password, you can gain insight about what the true hashes value is, and therefore begin to crack it. This is known as a timing attack.

Any time you're comparing values in a secure context, you should a constant-time algorithm. The time required for these is always relative to the length of the values, and doesn't short circuit. For example, like the following Python:

def constant_time_compare(val1, val2):

if len(val1) != len(val2):

return False

result = 0

for x, y in zip(val1, val2):

result |= x ^ y

return result == 0

(Please don't actually use this python, as it's not actually constant time. hmac.compare_digest is the one for you!)

Concluding

Storing passwords is pretty simple, right? Whilst the above sounds fairly complicated, in reality it's simple. The advice for now is only valid for now, for right now. In a few months, years or even days from now, this could all be obsolete. The best thing you can do is to not store passwords yourself and let someone else, someone who's up-to-date with security practices, to define it for you.

def encode(self, password, salt, iterations):

hash = pbkdf2(password, salt, iterations, hashlib.sha256)

return "%s$%d$%s$%s" % ("sha256", iterations, salt, base64.b64encode(hash).decode())

def verify(self, password, encoded):

_, iterations, salt, hash = encoded.split('$', 3)

encoded_2 = self.encode(password, salt, int(iterations))

return constant_time_compare(encoded, encoded_2)

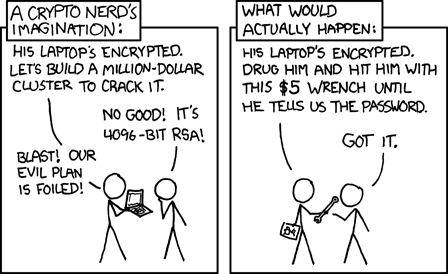

But of course, the strongest password and the most secure storage mechanism won't protect you from human error!